The two young girls set to work in the midnight cold, clad in nothing but underwear and high heels. Between them there are hundreds, if not thousands, of dollars to be made tonight.

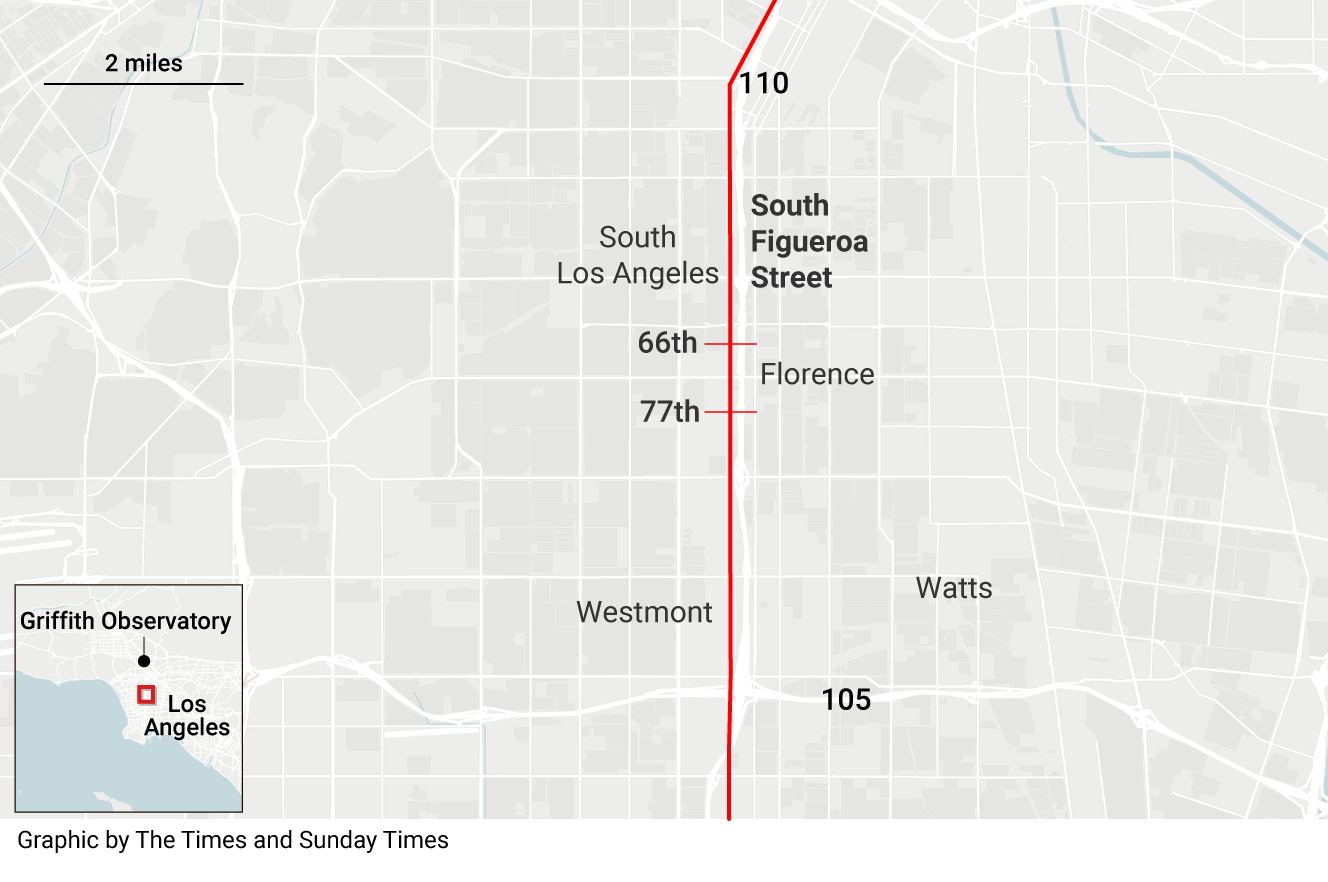

Unfazed by the sirens in the distance and a helicopter circling above, they beckon to the blacked-out cars that line Los Angeles’ Figueroa Street. This four-mile stretch of road, just south of the heart of the city, is regarded by federal authorities as the most notorious prostitution corridor in America.

In one of the idling cars sits Sergeant Al Navarro. He is confident the girls are underage but, due to a shooting a few blocks away, does not have any uniformed officers available to approach them and verify their age. Doing so himself could blow his cover and jeopardise his entire operation.

In one of the idling cars sits Sergeant Al Navarro. He is confident the girls are underage but, due to a shooting a few blocks away, does not have any uniformed officers available to approach them and verify their age. Doing so himself could blow his cover and jeopardise his entire operation.

“The number of juveniles out here has exponentially grown,” says Navarro, of the Los Angeles police department’s 77th Street station. As he drives away in an unmarked police cruiser he points out several other potential minors. “If I had two more black-and-whites I would stop her,” he adds. “Her, too.”

Figueroa Street has been associated with prostitution, shootings and murder for decades, but the authorities warn that it has taken an even darker turn in recent years.

Girls as young as 12, some tattooed with their pimp’s initials, are forced onto the street every evening to sell their bodies, police say. These minors are expected to make up to $1,200 every night. “If a girl meets her quota for the night, she can go home,” Navarro says. “If she doesn’t, she keeps on working.”

Figueroa Street has been associated with prostitution, shootings and murder for decades, but the authorities warn that it has taken an even darker turn in recent years.

Girls as young as 12, some tattooed with their pimp’s initials, are forced onto the street every evening to sell their bodies, police say. These minors are expected to make up to $1,200 every night. “If a girl meets her quota for the night, she can go home,” Navarro says. “If she doesn’t, she keeps on working.”

His officers rescued 123 children last year — a near eightfold increase from 2022. Run 2 Rescue, an anti-trafficking charity, says it recorded 100 interactions with children and young adults along the street in 2023. This rose to 250 last year, and in the first three months of this year alone has already surpassed 130.

Navarro estimates that for every child rescued, at least two more remain out on the street. “There’s been an explosion in numbers.”

The police stage one big undercover operation on Figueroa each month, which The Times was invited to join last month. For more than six hours, officers shadowed several pimps as they attempted to recruit young sex workers, including two undercover officers, before their eventual arrest.

In the busiest areas, half a dozen sex workers lined every block as drivers queued up to inquire about their services. Officers watched on from the darkness of their cars, relaying intel and looking for violations that would allow them to act. Those caught procuring women for prostitution face up to six years in jail; the trafficking of children for sex can result in a life sentence.

A decade ago, police would have arrested underage girls for engaging in commercial sex work. But attitudes have changed. “Now they’re viewed as victims,” Navarro says.

The police stage one big undercover operation on Figueroa each month, which The Times was invited to join last month. For more than six hours, officers shadowed several pimps as they attempted to recruit young sex workers, including two undercover officers, before their eventual arrest.

In the busiest areas, half a dozen sex workers lined every block as drivers queued up to inquire about their services. Officers watched on from the darkness of their cars, relaying intel and looking for violations that would allow them to act. Those caught procuring women for prostitution face up to six years in jail; the trafficking of children for sex can result in a life sentence.

A decade ago, police would have arrested underage girls for engaging in commercial sex work. But attitudes have changed. “Now they’re viewed as victims,” Navarro says.

The girls working Figueroa nearly always come from broken homes, local charities say. They are the children of drunken parents, or the victims of sexual assault. Some are orphans. Others are school drop-outs with minimal education. Most have fallen in and out of foster care.

In the days before the police operation, The Times observed the rescue of a 14-year-old girl who had run away from her children’s home in northern California. She had done so with another teenager, who beat her, took her phone and forced her into sex work.

Hannah — not her real name — was later driven by a pimp to LA, where she spent five days on Figueroa. She was raped in the street at one point and had a gun held to her head, before Children of the Night, an anti-trafficking charity, rescued her.

“I really didn’t know if I was going to live another day out there,” she said on the night of her rescue, slurring her words as she spoke. Her eyes were dilated and she walked with a limp. “I had to grow up so quick — I’ve been through so much.”

Social media has become one of the main routes into underage prostitution — especially since the pandemic, which drove even more children online and put those from troubled backgrounds into pimps’ reach.

Social media has become one of the main routes into underage prostitution — especially since the pandemic, which drove even more children online and put those from troubled backgrounds into pimps’ reach.

Amy, a former child sex worker, was 13 and living in a care home in San Bernardino when a woman sent her a message on Instagram in July 2020, asking if she and her 11-year-old sister wanted to make some money.

“We were being moved from one placement to another. None of my family members wanted us,” she said. “We were fending for ourselves so were like, ‘Yeah, sure.’”

“We were being moved from one placement to another. None of my family members wanted us,” she said. “We were fending for ourselves so were like, ‘Yeah, sure.’”

The woman turned out to be the “main girl” of a local pimp, and soon enough the girls were being moved along the west coast, from LA to San Diego to Oakland. For 18 months, Amy says, they were raped nearly every night by men — in the back of cars, hotels and abandoned homes.

“What I was doing out there, a parent should not have allowed me to do,” said Amy, who recently finished her school studies. “I didn’t know what was right from wrong.” Her sister continues to work on Figueroa, she said.

Shannon Forsythe, the co-founder of Run 2 Rescue, says all of the girls in her care home who had fallen into sex work were recruited via the internet. “Instagram and TikTok are hotbeds,” she said. “And online recruiting is still on the rise.”

Shannon Forsythe, the co-founder of Run 2 Rescue, says all of the girls in her care home who had fallen into sex work were recruited via the internet. “Instagram and TikTok are hotbeds,” she said. “And online recruiting is still on the rise.”

The decriminalisation of loitering for sex in 2023 has also been attributed to an increase in child sex workers on Figueroa Street.

Critics say the law has helped to grow California’s sex industry, emboldening pimps and their exploits, and fuelled demand for women of all ages and profiles. It has also slowed efforts to remove juveniles from the streets as there are not enough police officers to stop and age-check every sex worker who looks under 18, Navarro says. “It’s not going to happen.”

On a good night, an undercover operation run by Navarro will rescue as many as three girls from Figueroa. But they are not always willing to co-operate with the police. Many will refuse to answer questions and run back to their pimps once they are passed into the care of LA’s child services department. Navarro calls these cases “pretty disheartening”.

But he and his colleagues remain undeterred, venturing out in their uniform to Figueroa every week.

“I’m used to the rollercoaster,” he says. “You have to be able to deal with frustration to do this kind of job, because there’s a lot of it. But there’s also some reward.”

“I’m used to the rollercoaster,” he says. “You have to be able to deal with frustration to do this kind of job, because there’s a lot of it. But there’s also some reward.”